On September 29, 2017, ACDIS and the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies (CSAMES) hosted the symposium, “Shifting Iran-US Relations: Return to Status Quo Ante or New Alignments in the Middle East Region?” Speakers included Asef Bayat, Shireen Hunter, Kevan Harris, Frederick Lamb, Matthias Grosse Perdekamp, and Trita Parsi, Founder and President of the National Iranian American Council, who gave the keynote speech. View the program here.

Commentaries on Iran Policy

By Trita Parsi:

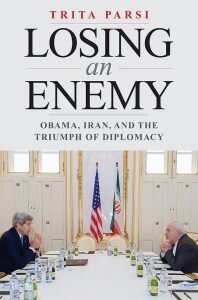

Roundtable 10-7 on Losing an Enemy: Obama, Iran, and the Triumph of Diplomacy in the International Security Studies Forum (January 25, 2018)

Cotton, Pompeo And Trump Are A Recipe For War With Iran in Huffington Post (November 30, 2017)

5 Reasons Why Trump is Moving Towards War with Iran in Huffington Post (October 12, 2017)

Iran: Trump’s Gift to the Hard-liners in New York Review of Books (October 10, 2017)

The Real Risk in Trump’s Iran Gambit in Fareed Zakaria’s Global Briefing, CNN (October 9, 2017)

By ACDIS affiliates:

The Iranian Dossier – France’s Position by Maxime H. A. Larivé (October 27, 2017)

The United States Lacks Leverage to Re-Negotiate the Iran Deal by Nicholas Grossman (October 9, 2017)

Trita Parsi, Founder and President, National Iranian American Council

You recently published a book just in August. What inspired you to write that book? What is it about?

It’s called Losing an Enemy. It’s about not just negotiation between the U.S. and Iran nuclear issue, but the longer history of U.S-Iran tensions, and that’s why it’s called Losing an Enemy. It’s about the process of actually trying to end an enmity, or the opportunity to do so.

The reason I wanted to write this book is because I was advising the White House on nuclear talks, so I had a bit of a front seat privilege to see what truly was an international crisis on the verge of military confrontation being resolved without a single shot being fired, without an angry 4 a.m. tweet being shot off, and it worked!

We don’t have a lot of stories of that kind. We have a lot of sad stories – a lot of stories of how we had to use our military, but not one in which we truly ended with diplomacy, with positive results.

Because the United States is a superpower, and because superpowers seem to have very strong militaries, we tend to approach international conflicts from a military perspective. Our capacity and our instinct to pursue diplomacy has significantly weakened over the course of the last 20 years. In this particular case, we had to use diplomacy and diplomacy is tough, it takes time. You cannot just strong-arm and get your way. You actually have to have some patience; you actually have to have a give-and-take. Certain current politicians don’t seem to fully have grasped that

What was it like being a policy advisor for the Obama administration?

I was an informant advisor. We very passionately worked for the diplomatic sector during the Bush administration when we had no one at the White House at the time that would necessarily listen to us. But we kept on at it because we knew that we were right. We weren’t changing our strategy just because it wasn’t temporarily successful. We pursued the path that we knew would be the best for the United States regardless of the immediate impact or immediate success we had.

By the time the Obama administration decided that this was the path, they wanted to go through we were one of the clear potential partners in Washington D.C because we had stuck with our mission during the toughest of the toughest times.

It was truly an amazing experience because it was one of the biggest shifts in U.S. policy in the Middle East that we’ve seen in the last 30 years. We saw things up front that were completely taboo in the past being broken left and right and the U.S. and Iran were doing things together. Both had fought just 6 months ago; it would have been political suicide for him (Barack). It was truly amazing and that’s part of the reason I wrote the book – because I had that front seat privilege.

Do you have any advice for young professionals or students who are interested in making changes in policy, working with organizations like yours, or beginning their own?

Oh, absolutely! I hope more do because change doesn’t come unless you have people organizing it and doing it passionately. So, if there is anything I would recommend it is to come to Washington D.C with an open mind. Learn how it works, but then don’t lose your passion. Don’t get attracted to power, get attracted to the opportunity to be able to make a change. That does require tremendous amount of passion.

Kevan Harris, Professor of Sociology, University of California-Los Angeles

Could you talk about the research you’ve done, what inspired it, and how that has led up to the book you just published?

I’ve been traveling to Iran since 2006, so I’ve gone there over multiple presidents and across lots of different cities in Iran and even some villages. As I was traveling around Iran and I started to see a lot of things that I never read about in media, by journalists, or even by other scholars who’ve read about Iran, so these opened up some questions for me about how did life bring about change since the 1979 revolution, and what did the changes in Iran come about from the ground up, how did that affect the kind of politics in Iran that we saw today.

I was in Iran in 2009 when a famous social movement took place, the Green Movement, which was a movement that was protesting the results of a presidential election in 2009. I saw this movement with my own eyes. So I started to think about how did the transformations in state-society relations affect the ways that these social movements formed in Iran. So I’ve been looking at the welfare state in Iran. Why the welfare state? Because a lot of people in Iran were protesting and were educated at public universities, or their fathers had been fighting in Iran when the war took place in the 1980s, and because of their relations with social policy they ended up becoming educated and also politicized.

The book I wrote was an explanation on the ways in which the Islamic republic intervened and then used social policy, education policy, health policy, other types of welfare policy, after the revolution how that changed society, and then how social movements rose out of that changed society to then make new claims with new demands against the government. I tried to show others the link between both ways that the revolutionary state made policy and the ways social movements then pushed back against the government. My book has just come out in 2017, and it’s called The Social Revolution and it's about this process.

Then I decided to do a couple of new projects, one of which is on business state relations in Iran and one is on these issues with mobility.

Now that you just finished your book in August, what are you doing now?

Well we just did a very large social survey in Iran. Meaning that you call people on the phone and ask a bunch of questions. It’s like the United States. There have been a fair amount of surveys done in Iran but we have done something different, which we’re calling social surveys. Instead of asking people’s opinions about things we’re trying to ask about people’s relations with other people, with other organizations, and also about their family history. That’s pretty important because we’re asking about what their parents did and what their grandparents did because Iran, like a lot of developing countries, has gone through huge transformations in the last 50 years.

Urbanization, the shrinking of the family size to basically the nuclear family size now, the massive education of men and women — to women the same rates as men in Iraq. We still don’t know a lot about the implications of these changes. You can go to Tehran for example and see all of these educated people walking around, and politics and opinions, and were talking about everything. But a lot of what gets reported is usually anecdotal or it comes from official sources, or from, let’s say opposition sources.

We did a big survey and we asked a lot of questions about these families and we have to think it’s representative of the entire country. From that we can say a bit more about, let’s say, what’s the likelihood of women getting educated in Iran assuming their mothers were educated in Iran? And we can look at those big transformations and sort of map out how these happen. We did that about a year ago, in December 2016, and now we have all the survey information and we’re going to be writing about it.

Do you have any advice for young professionals or students who are interested in making changes to policy or doing research more effectively?

In policy, relevant research is kind of an oxymoron because you never know what research ends up being read by policymakers. The best way is to learn how to write clearly and also know your audience. Ultimately nobody reads academic articles. That’s just something you learn you have to accept as a professor. But what you can do when you do a piece of original research is kind of boil that down into a smaller, digestible piece and make sure that it gets places and then it’s really about contact so if you have people who both you respect and they trust your work, that work can then get a wider audience. So basically you just – its really not that different than any other kind of thing – You network. If you really want your work to be read by anybody, then network. Unfortunately just because you’re a genius and you write something, standing alone by itself doesn’t necessarily give it an audience.